Since That Day(Picture book)

Since That day

-by NAGANO Hiroaki

My name was Kanazawa Etsuko at that time. In 1945, I was 16 years old.

I had a sister called Kuniko who was 13 and a brother, Seiji, who was 9. Kuniko and Seiji died through the atomic bombing Of Nagasaki.

To tell the truth, neither of them should have died. It was all my fault.

On the morning of August 9, 1945, the air raid sirens sounded and everyone ran to the air raid shelters, but after a while we were given the all clear and I went to work as usual, leaving my siblings and mother at home.

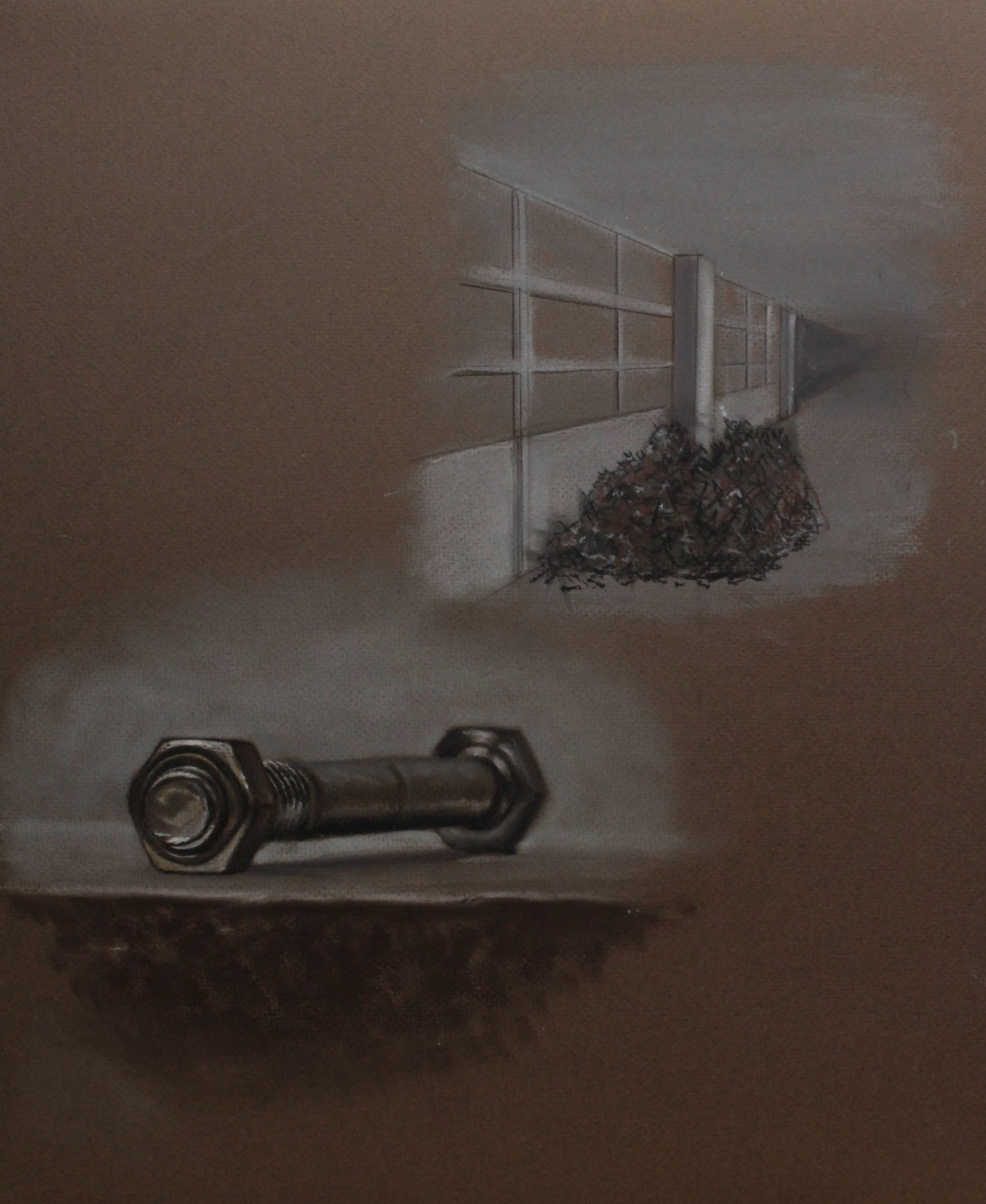

It was a very hot day at the height of the summer. As a mobilized student, I was a lathe-worker for the local Mitsubishi Electric factory, making airplane parts in the gymnasium of Nagasaki University Economics Department at what is now Katafuchi-machi. The gymnasium was 2.8 kilometers from what became ground zero of the atomic bomb. Many of the nuts and bolts we made were defective and there were heaps of them piled up in the corridor.

At 11:02 a.m. the United States B-29 bomber “Bockscar” released a single atomic bomb above Urakami Cathedral in Nagasaki.

With heat rays of 2,000 to 3,000 degrees Celsius, the blast blew up everything, and humans, plants and animals were carbonized.

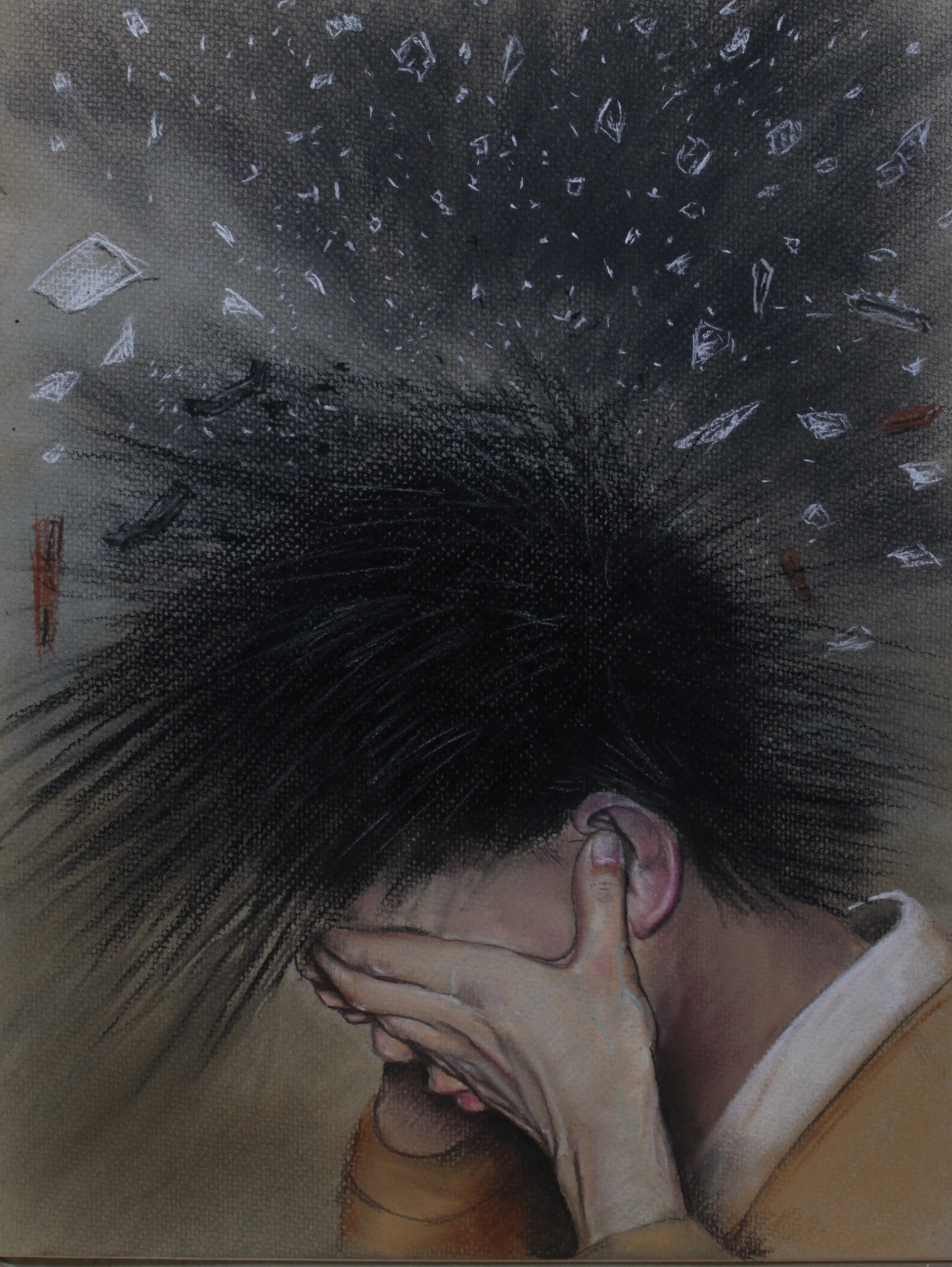

At the gymnasium where I was working, around 11 o’clock, a blinding flash appeared in the windows. Then, suddenly, there was darkness and the sound of shattering glass. At once, I covered my ears with my thumbs and my eyes with the other four fingers and threw myself to the floor. My mouth filled with dust and grit and I could not open my eyes.

One of the workers called my name and said, “The whole of Urakami district is destroyed! Your house has probably burnt down! Go home right away!”

I hurried home. On the way, when I reached Nagasaki Station, I looked towards Urakami. The rows of wooden houses had all collapsed, flames were leaping out here and there and there was not a trace of roads. Because of the fires, I could not make straight for Urakami, so I decided to take a detour west and cross the Inasa bridge.

Amazingly, on the bridge I found my father on his way home from Mitsubishi Electric and we fell into each other’s arms crying and rejoicing for our survival. Then, we set off together, along the bank of the Urakami River, to Takenokubo-machi in search of the rest of our family.

On the bridge over the river at Mori-machi I saw the blackened corpse of a horse, still standing.

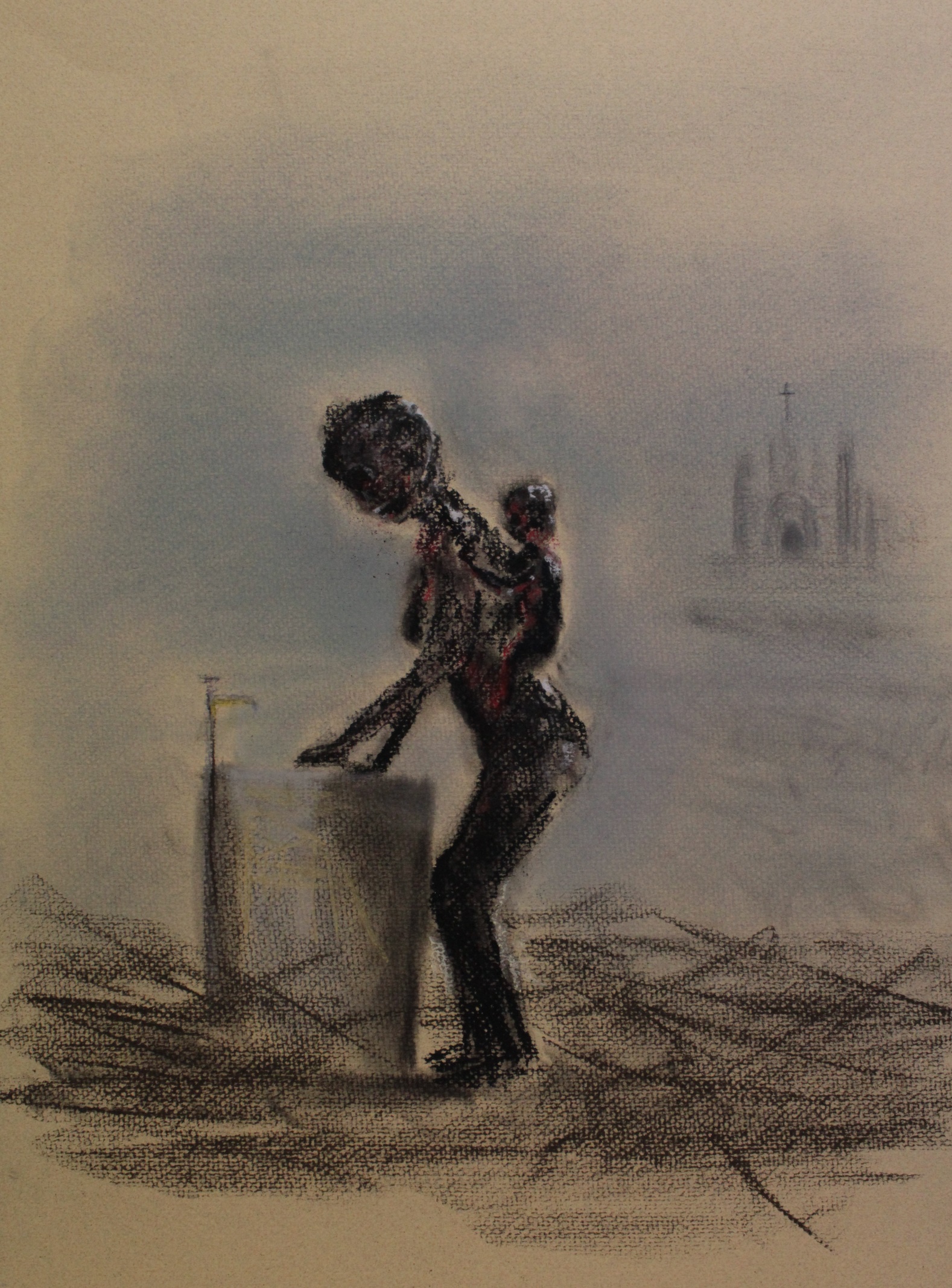

I also saw a terribly burned and carbonized mother with a baby on her back, still leaning at the sink of a collapsed house.

There were hundreds of corpses scattered about, of those who had fled from Urakami. Survivors, blistered with burns or almost naked with the scorched tatters of their clothes clinging to their skin, were staggering left and right. There were countless bodies piled up along the banks of the Urakami river. Dying people begged us for help and water, but my father and I could do nothing. They all looked like ghosts, burnt and wandering about. Still now, I feel that the day the atomic bomb fell on Nagasaki was a living hell.

The next day, August 10, my father and I walked to our neighborhood although the ground was still burning with embers. The first thing that caught my eye was the charred figure of an adult lying near the smoldering ruins of our house. Thinking that it was my mother, I leaned over and clung to the blackened corpse crying, “Mom! Mom!”

Then one of my friends told me that my brother had suffered burns and was lying in a nearby air raid shelter. “I’m sorry I couldn’t do anything,” he said. Hearing this, my father and I hurried around the various air raid shelters in the neighborhood, looking into each and calling my brother’s name, “Sei-chan! Sei-chan!”

Eventually, we found my brother lying at the entrance to one of the shelters. His body was covered with burns and his face was swollen with blisters, making it impossible for him to open his eyes. On his name tag, which remained on the burnt skin of his chest, you could just about make out, “Kanazawa Seiji, blood-type B, grade four elementary school pupil, age 9.” When my father tried to pick Seiji up, the blistered skin of his arms peeled off in my father’s hand. My father found a wooden storm shutter in the ruins of a fire. We lifted the injured Seiji onto the shutter and carried him, encouraging him constantly, “Hold on! Hold on! Sei-chan!” to a first-aid station, but all they could do for him was paint him with zinc ointment. We were on the way back to the shelter again with my brother on the shutter when we were shocked to see my mother and my sister walking, looking exhausted.

My mother was alive after all! Seeing her son so mortally wounded, she clung to him and sobbed hysterically.

Seiji had left the house saying that he was going to catch dragonflies. My mother and sister had been buried under the collapsed house, but they had managed to free themselves. Although worried about Seiji, my mother could only take Kuniko and flee up Mount Kompira. There, they had spent the night waiting until dawn before starting back down again.

My brother seemed relieved to be reunited with us all and to be able to spend the night together in the shelter.

He died on August 11 whispering, “I’m thirsty. It hurts. It hurts.” If the air raid warning had been kept in force, many people, including my brother, would have stayed in the air raid shelters and might have survived.

We piled scraps of wood above the corpse of Seiji, and cremated him by ourselves. My mother screamed “I want to die with Seiji!” and tried to jump into the fire but we stopped her with our crying.

On August 15, word went around that the war was over and that Japan had been defeated. I could

not help thinking that, had the war ended sooner, the atomic bombs would never have been used, there

would have been no need to send kamikaze pilots out on suicide missions and many deaths would

have been avoided..

On August 16, we walked 50 kilometers to my father’s hometown of Obama. My mother scooped Seiji’s ashes into a rice bowl she found and carried it carefully with her hand over it so as not to spill what remained of her son.

Even after we moved to Obama, my sister Kuniko, whenever she heard the sound of an airplane, hid, crying and trembling under a futon. She was so frightened, for she did not believe that the war was over.

Kuniko died of atomic bomb disease on September 10, one month after the bombing.

Kuniko began to lose her hair, to develop spots all over her body, to bleed from her gums and to suffer bloody stools. Finally, she died crying in pain. A week later, my mother also developed spots on her body and was admitted to hospital in Obama for about a month, but she lived on to the ripe old age of 93. Although they had both been exposed to the same conditions, the results were obviously different. What a cruel weapon the atomic bomb is to affect children more severely than adults.

My father died in 1948 after three years of the atomic bomb. My mother had blamed him “If you had let Kuniko and Seiji be evacuated to Shimabara, they need not have died!” But, really, I think that my mother thought I was to blame.

Before the atomic bomb was dropped, we had some trees of loquats, figs, pomegranate and mikan

oranges in our garden in Zenza-machi. We used to enjoy climbing a tree and eating the fruits.

But then Kuniko and Seiji were sent away from Nagasaki.

After Japan attacked China, and Pearl Harbor in the United States of America, the war had expanded

and American bombers had bombed Japan. So, Kuniko and Seiji were evacuated to my grandparents’

home in Kagoshima about a year before all this.

I felt so lonely without them that I begged my mother every day to let my brother and sister come home.

She said I could go and see them, but she warned me, “They probably have a lot of friends in Kagoshima

so do not bring them home if they do not want to come.” “Yes Mom!” I said, then went off to Kagoshima

by myself on the train.

When I got to Kagoshima, the two of them both cried and said, “We don’t want to go back to Nagasaki because we have a lot of friends here!” My grandparents also opposed me. Nevertheless, I forced my siblings to come back home with me. That was 4 months before the atomic bomb.

When I got to Kagoshima, the two of them both cried and said, “We don’t want to go back to Nagasaki because we have a lot of friends here!” My grandparents also opposed me. Nevertheless, I forced my siblings to come back home with me. That was 4 months before the atomic bomb.

Even now, I regret that I broke my promise to my mother and brought Seiji and Kuniko back from Kagoshima against their will. They said, “We don’t want to go back to Nagasaki!” but they were killed by the atomic bomb, whereas I, on the other hand, survived. Even now, I still wish that it had been me instead of them. I apologize to my parents, my brother and my sister every day. “It was my fault and I am very sorry,” I say, joining my hands in prayer in front of our family’s Buddhist altar.

Although my mother never openly blamed me, a frost grew between us as we each carried our private burdens of loneliness. Around a week before she died, my mother suddenly said, over and over, “Etsuko-chan, I am sorry.

I owe you a lot.” When I heard that, I understood that she was forgiving me. I sobbed my heartfelt apology, rubbing the hands of my old mother in her hospital bed, “I was sorry, Mother. I should not have forced them to come back to Nagasaki and I let them die. I am so sorry.” She died in her sleep about a week later.

Now, I have two great-granddaughters. I do not want these children’s lives to be sacrificed for any war.

Japan is the only nation to have ever suffered the devastation of atomic bombs. I pray for the peaceful repose of the souls of all those who perished in the war. I hope that Japan will lead the way, and I pray that the day will soon come when there is an end to all wars and a complete abolition of nuclear weapons.

The Explosion of the Atomic Bomb and the Damages It Caused

At 11:02 a.m. on August 9, 1945, an atomic bomb was dropped and exploded in the air at a height of 500 meters above northern Nagasaki City – 171 Matsuyama machi.

Nagasaki City on August 9, 1945

Population: about 240,000

Deaths and injuries caused by the atomic bomb

(estimates up to the end of December 1945)

Deaths : 73,884

Injuries : 74,909

Houses entirely burnt down : 11,574

Houses entirely destroyed : 1,326

Houses partially destroyed : 5,509

Land Completely Levelled : 6,702,300㎡

(quoted from The Records of The Atomic Bombing in Nagasaki)

あの日から

Since That Day

Desde Aquel Día

絵 / 永野博明 Picture: Hiroaki Nagano

文 / 金澤悦子 Text: Etsuko Kanazawa

訳 / 永野博明 Translation: Hiroaki Nagano

英語監訳/ 坂本季詩雄、Felicity Greenland

Supervisor of English Translation:

Kishio Sakamoto, Felicity Greenland

スペイン語監訳/ 牛島万、Kótaro Yanagi Ortega

Supervisor of Spanish Translation:

Takashi Ushijima, Kótaro Yanagi Ortega